| |

|

The relation between

architecture and cinema

began more than a century ago with the production of the very first films.

There is architecture in almost every film. Consciously or not, architecture

takes its position as an effective element in films; architectural space

influences what is shot. If it is possible to argue that cinema is under the

influence of architecture, then it should also be stated that architecture

discovered cinema. Cinema became a domain of inspiration for architecture

especially in the late twentieth century. Now we may hear an architect

saying a film has been influential on his design or see some new notions

brought by cinema integrated into a building.

Most

of the art forms such as painting, theater, ballet, literature, poetry,

photography, cinema, including architecture, try to describe or create

space. While space is a tool in cinema and the other forms, architecture

uses art to make space. Space, whose creation is an artful act, is the

product of architecture. One significant difference is that space is the

foreground in architecture since it is the purpose and the reason of its

existence. In cinema, the purpose is not necessarily to define or create

space, however space is one of the inevitable elements like script, music,

light and actors. In architecture, space is what you

design and

build for. Despite different perceptions, space is a shared concept for both

architecture and cinema. A novel, a piece of music, a painting and a

photograph can exist without the concept of space but a film cannot. Cinema

depends on space (some ‘abstract’, usually animated, films are excluded).

Film, as Lorcan O´Herlihy says, tells “spatial stories”: “The idea that

the movement of a body through

a constructed space and participating in its narration lends itself to a

more intimate union between film and architecture,”

(1994: 91).

Cinema represents architecture, space, time, a person, an object, a story,

an ideology, an event or a feeling. Film space can be seen as a

representation

of architectural space. What is represented in a film is about

architecture, but it is not architecture itself. It is not its copy either.

It is rather an interpretation of architecture. Just like films as “representational

pictures” (Carroll, 1988: 98) are not the copy of the real, film space

is not the copy of real space rather it is something new and different; it

has its own reality.

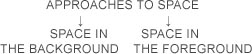

Table 1.

Approaches to space in cinema

In most films, space is in the background (Table 1). Most directors are

neither concerned of the representation of space nor benefit from it as a

tool effectively. Bowman says, “I don’t think that directors and their

collaborators necessarily think about how they are going to arrange scenes

spatially,” (1992: 4). These directors select spaces not as to the

contribution of space to the film but due to its propriety for shooting such

as light conditions or camera location. Therefore the name of this group, ‘space

in the background’, has a metaphorical meaning. Space, in these films,

is not a notion in the foreground. Another reason for choosing this name is

literal: The space is physically in the background in these films. It is

there, behind the action as a backdrop. It fills the empty parts behind

actors in the solid cinematic frame.

Directors, who are considered to be the members of the ‘space in the

foreground’ group, on the other hand, analyze, uncover, and transform

space. They are interested in the representation of architecture and space

in their films. They are aware of the potentials of space and make use of it

by examining it and looking for its limits. Space, as an actor, is

metaphorically and literally ‘in the foreground’ in these films. Space acts.

Bart Mills says, “The setting is the film,” (Sobchack, 1987: 262).

German director Wim Wenders belongs to the second group; space is in the

foreground in his films. He has a distinct approach to filmmaking and space

both of which are significant when the representation of architectural space

is concerned. The films he makes are important examples when the interaction

between architecture and cinema is concerned. This study aims to

uncover the relation of representation between architecture and cinema

through Wenders’ films, focusing on the conception and shifting meanings of

space.

Wenders’ approach to filmmaking

It seems hard to consider Wim Wenders as a member of a style. The

cinema of this contemporary director who made his first film in 1967 belongs

to “a cinéma des auteurs, a cinema created by filmmakers who, to use

François Truffaut’s famous phrase, write “in the first person”” (Paris,

1993: 31). Wenders approaches filmmaking and space with an artistic

sensitivity. He is famous for his road films.

Wenders’ attitude to filmmaking is selective. Even music is selected

(from his favorites). Like a camera framing space that breaks space into

pieces, Wenders selects pieces from the chaos of life and creates a whole

combining them. He aims wholeness in narration, but not in what he narrates.

Wenders tries to understand our chaotic lives and expresses his view on life

through cinema. He shows and interprets this chaos. The order is never

totally designed or artificially constructed; it is natural. He forms the

film not on paper but during the shooting. Everything is not planned in the

script. Improvisation is appreciated. The film finds its way during the

shooting.

Both as an artwork and a representation, film has a new reality of

its own. It has a reality independent of what it represents. What is

on the screen is real (cinematic reality). Wenders invites the viewer to

identify himself with the subjective camera. The viewer is there in the

hotel, the circus, the city, the car or on the road. Wenders wants the

viewer to believe in him, to feel himself as part of the film. The camera is

like a character in the space. The massage is represented through emotional

involvements.

When filmmaking is concerned, Wenders is a ‘filmmaker as a filmmaker’. He

uses the possibilities of the cinematic medium – not references from other

art forms – to make films. Cinema for Wenders is both a form of art and a

mode of representation. His films are artworks but representation as

interpretation, rather than art, seems to dominate in his cinema. Content is

superior to form. Form is always for the content. His primary aim is to tell

stories; Wenders is a story-teller.

Wenders’

approach to space

|

|

Figure

1

‘Kings of the Road’

|

|

Symbolization of architecture as a tool for the film can be considered as a

characteristic of Wenders’ cinema. His use of space is symbolic.

Space in his films symbolizes some aspects of the film or the story,

especially the society. In his road films such as ‘Alice in the Cities’

(1974), ‘Kings of the Road’ (1976) and ‘Paris, Texas’ (1984),

the city is the symbol of the modern man who ‘lost touch with the world’

and the road is the symbol of the ‘moving man’. His characters prefer

moving and leaving to staying (figure 1).

Moving is a way of living. It is what being at home means. It is not only

his characters who move. Wenders states he himself can work only when he

travels.

When used as a symbol, space is treated as a basic element of the film like

an actor, script or music where the treatment is functional. In other words,

here space, which is in the foreground, is a tool to convey the message. It

helps the visualization of narration. The representation of space is mostly

physical (audiovisual) in character whereas the use of space is generally

symbolic or metaphorical. Space symbolizes things such as a person, an event

and a situation for narration. Meanings are represented by symbolized

architectonic elements.

Space in Wenders’ cinema has a social character as well. His approach

to space, film and life is social. He uses cinema to express his

understanding of society. For him, space is part of the chaotic social life

and is the reflection of the society. Instead of its physical form, he

focuses on the social aspect of architecture, on its place in people’s

lives. His aim is to tell how he sees people and the society using space

(human - space relations). That is the way he represents space in film.

Wenders’ approach to space, as to film, is selective. “It is a

selective landscape that we see,” (Harvey, 1990: 316). He selects and

analyzes a particular space and turns it into a symbol. He selects pieces

out of the chaos of architectural space, frames them due to his aim,

transforms them using the possibilities of the medium of cinema and forms an

order. Space in Wenders’ films is a visual tool for the story.

Both spaces and spatial experiences are designed in Wenders’ films. He

prefers using real (existing) spaces (road, city) to film sets. The

interior spaces represented in Wenders’ films are not many in number; they

usually are cold, ordinary hotel rooms, cafes and gas stations. They are

always instantaneous, temporary and foreign. Hotel is the space for a break;

Wenders himself writes and evaluates there.

Unlike architecture, both space and time are designed in the medium of

cinema. As for the films of Wenders, time is usually linear like the

movement of his characters on the road. Film is like a journey that starts

in the beginning of the film and ends in the end. Architectural space that

is continuous by nature becomes discontinuous in Wenders’ films as in

almost all films. Framed pieces of space are recontextualized through

montage. Normally cinema flattens space. It carries architectural space from

three-dimensionality to two-dimensionality. However, at the same time,

cinema creates the ‘impression’ of the third dimension which is depth.

Wenders’ camera usually tries to create the sense of depth.

There are several techniques and elements that the director uses in the

representation of space in his films. He uses most of them in every film.

The possibilities and limits of his symbolic/social space are analyzed

through these techniques and elements in his films.

Spatial techniques

Use of movement: Space is in motion in Wenders’ films, especially in

his road films. He prefers using mobile frames, and space gains dynamism.

Characters are never ‘there’; they pass by; they move through

spaces. Space is perceived while moving. The camera moves to keep something

mobile in sight such as a plane, a flying bird or a boy riding his bicycle.

Moving is a way of living. Wenders shows us a new way of perceiving space.

Use of black and white: Wenders prefers black and white films to

colored ones. While shooting Hammett (1978-1982), his first film in

the United States, he was not allowed to use black and white, therefore he

made the darkest film ever. The use of black and white together with color

as a technique to represent space dominates in ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’.

Use of light: Wenders usually uses natural light (daylight) or city

lights, especially on the road. Nothing but light, such as the neon lights

of a hotel or a city, is perceived while driving at night.

Framing: Wenders uses cinematic frame to (de/re)contextualize space.

He uses a framed piece of space which is detached from its context to create

new architectural or cinematic meanings. Wenders selects spaces with his

mobile camera. The space continues behind the frame. For this reason, space

in his films is the totality of onscreen and offscreen space.

Superimposition of images: Wenders superimposes and juxtaposes images

within the cinematic frame in ‘Notebooks on Clothes and Cities’ (1989). In

this ‘diary-movie’ that is about a Japanese fashion designer living in

Paris, the juxtaposed images represent the process (sewing a dress that is

tried on by a model), the product (fashion show) and the theory of design

(the designer’s words) at the same cinematic moment. The shape and the

location of the frames on the screen match with the content of the frames.

Spatial

elements

|

|

Figure 2

‘The State of Things’

Figure 3

‘Paris, Texas’

Figure 4

‘Paris, Texas’

Figure 5

‘Kings of the Road’

Figure 6

‘Paris, Texas’

Figure 7

‘Kings of the Road’

|

|

Road: A significant characteristic of Wenders’ cinema is his road

films. Most of his films take place not in the city but on the road - not

in but through a space (figure 2).

The road keeps characters away from the nastiness of settled life.

Characters belong to the road, not to the city. The road represents

‘seeking’ (figures 3, 4).

City: Road films turn out to be city films through Wenders’ camera.

Cities are like balloons attached to the edges of roads. They are for a

break while passing by. Not the elements – cities – but the relations –

roads – between them are emphasized. A city is represented simply as a road

and a void framed by the facades of the buildings along the road. Buildings

are the two-dimensional décor of the road as in Westerns (figure

5). In ‘Alice in the Cities’, cities instead of countries are in

the foreground. All the American cities look the same except New York that

has an identity with its high-rise buildings.

Vehicle: Characters – and the viewer – experience the city in a

vehicle in Wenders’ films. The camera frames the road and the city in motion

through the window of a vehicle such as a car, a train, a plane, a bus, a

boat, a bicycle or a ferry (figure 6).

There are public and private vehicles just like public and private spaces.

Private ones are usually ‘mobile homes’, for instance a caravan (figure

7). In his article about mobile homes Greg Metcalf mentions the

ones in ‘State of Things’, ‘Paris’, ‘Texas’ and ‘Der Himmel

über Berlin’.

Wenders’ techniques and elements of space not only turn space into an actor

but also make space a symbol of contemporary society. The changing character

of architectural space is questioned. Wenders’ way of representing space can

be considered as a tool for architects to analyze the social aspects of

space.

|

| |

|

‘Der Himmel

über Berlin’ (‘Wings of Desire’)

The king of the road wants to mount the

stairway to heaven.

Phillip Kolker and Peter Beicken (1993: 160)

Following the introduction about Wenders’ film space, the director’s

thirteenth feature film will be studied in detail to go further on the

subject. ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ that he made in Germany in 1987 is a story

of the city of Berlin and an angel in the city who wants to be a human

being. Space is a symbolic tool for story-telling in this film.

Berliners are not the only inhabitants of the city in ‘Der Himmel über

Berlin’.

Other than humans, angels live in the city. They are not visible to humans

but children notice them, yet in the next moment they forget about them. One

of these angels, Damiel, makes up his mind to become a human. He shares his

desire with his partner, Cassiel. Meanwhile he falls in love with a trapeze

artist, Marion, who works in a circus. According to an interpretation,

because of love, probably because of great desire his wish “to come

inside” (Harvey, 1990: 319) turns out to be true. There are two other

characters that are successfully integrated into the film, Peter Falk (as

Peter Falk) and Homer. Falk, who was an angel once, is in Berlin to act in

an American film about the Nazi period. Homer as the story-teller, on the

other hand, looks for his listeners who became readers far away to tell them

the past of Berlin. The ‘hi(story)’ must be remembered. “Homer is the

representative and bearer of collective memory, the spirit of history. He is

also the spirit of Berlin, who laments the vanishing of the city in the war,”

(Kolker and Beicken, 1993: 151). It is a pity that such an inspiring film

has been reduced to a love story in the last scenes (with Marion’s

theatrical monologue).

In one of the scenes, the viewer sees a raving man about to die near a

bridge. As the man raves (as his thoughts swing in his mind), the camera

swings like a pendulum, and as it swings, the viewer sees the parapet on one

side of the bridge and then the other. The changing perspective of the

bridge as the camera swings emphasizes the thoughts flying in the mind of

the dying man, and it seems to symbolize his journey between life and death.

This scene is a good example of ‘space as symbol’ where space

is a tool to visualize and support what the director wishes to express.

There are two reasons for using the German title ‘Der Himmel über

Berlin’ in this text instead of the English ‘Wings of Desire’. One reason is

that Berlin has a very important role in the film: As Harvey states “it

is a pity that

Berlin

disappears from the English title because the film is a wonderful and

sensitive evocation of the sense of that place,”

(1990: 314). The other reason is the double meaning of ‘Himmel’, sky and

heaven: As Wenders says, “In German the word ‘Himmel’ means both sky and

heavens so it was almost like a little poem, a little haiku,” (Paneth,

1988: 4). About shooting the film in Berlin, Wenders says:

It is the first time I made a film in one place. I really used to think I

was able to work only while I was on the road. It was scary to stay in one

place. But it wasn’t difficult at all, because there was a lot of other

movement. There was a strange movement in time which felt almost like a

journey. Of course, the film was not linear, like the other movies I’ve

made, where there was an itinerary. They always had horizontal movements.

‘Wings of Desire’ is my vertical road movie (Fusco, 1988: 16).

Wenders explains the origin of his angels as follows: “First

and foremost,

[Rainer

Maria]

Rilke’s ‘Duino Elegies’. Paul Klee’s paintings too. Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel

of History’. There was a song by the Cure that mentioned ‘fallen angels’,

and I heard another song on the car radio that had the line ‘talk to an

angel’ in it,”

(1991: 77). Wenders’ angels cannot feel but they hear any sound, even the

thoughts of humans. Life, for them, is to walk around and to collect

knowledge. They watch humans. Humans, on the other hand, ‘feel’, do not

‘watch’. They ‘live’ any aspect of life with their feelings. Angels cannot “get

inside the problem of human decision-making;” they “can never really

participate, only pretend,” (Harvey, 1990: 315). As Harvey says, “Being

outside human space and time, all the angels can do is to offer some

spiritual comfort, try to soothe the fragmented and often shattered feelings

of the individuals whose thoughts they monitor,” (1990: 315). Angels are

assumed to know everything. Humans, on the other hand, have the capacity of

'guessing' instead of 'knowing'. “Perhaps the ‘all-seeingness’ of the

angels was truer than the colorful, three-rather-than-four-dimensional

vision,” (Wenders, 1991: 82).

Angels see the world through “monochromatic eyes” (Harvey, 1990:

315), whereas humans have a colored world. The “use of color

changes to denote changes of viewpoint” is impressive in the film

(Green, 1988: 129). “They

[Angels]

know this place from time immemorial, and they are intimately acquainted

with its history,”

(Green, 1988: 128). Wenders says “the angels were a metaphor for history

and the memory of it,” (Fusco, 1988: 16). They are the witnesses of the

whole history of Berlin as Wenders states:

They

[Angels]

were there before the city was there, when there were still glaciers. They

saw the city being built, they saw Napoleon come through. They saw the city

being destroyed. They saw it all go down the drain. They saw it at its most

terrifying, as the capital of fascism. They are witnesses.

(Fusco, 1988: 16).

In ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, angels and humans are the users of

space – any space within the city. They conceive the world, life, time

and space in their own ways. Angels are always everywhere, whereas humans

are at a single place at a certain time. Harvey mentions “the

monochromatic landscape of eternal time and infinite but fragmented space”

(1990: 321) of angels saying “[t]he

picture of Berlin that emerges from their perspective is an extraordinary

landscape of fragmented spaces and ephemeral incidents that has no binding

logic,”

(1990: 315). Contrary to Harvey’s idea about the fragmented space of the

angels, the world is an unbroken, undivided space with the angelic

perception, just like the perception of children (world as one). However,

humans have “a totally different mode of spatial experience” (Harvey,

1990: 319); their world is broken into pieces. “In ‘Wings of Desire’, we

similarly encounter two groups of actors living on different time scales.

Angels live in enduring and eternal time, and humans live in their own

social time and, of course, they each see the world very differently,”

(Harvey, 1990: 314). Angels do not have limitations of space and time

just like memory and cinema. But, humans have 'now' instead of ‘always’,

'here' instead of 'anywhere'. Harvey says (1990: 315):

They

[Angels]

can also move effortlessly and instantaneously in space. For them, time and

space just are, an infinite present in an infinite space which reduces the

whole world to a monochromatic state. Everything seems to float in the same

undifferentiated present.

The spaces

In ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, specific elements in different scales are

defined for the representation of architectural spaces in Berlin; these are

the city, the Wall, the library and the circus. Berlin has a scale

which belongs to a city, the Wall is also in urban space scale, and the

library is represented in interior space scale, whereas the circus is in

both building scale and interior space scale. They are perceived sometimes

in black and white through the eyes of angels, sometimes in color through

the eyes of humans.

Berlin forms the general framework of the film. It is a symbol of

the fragmented postwar life which includes all other symbols driven in the

film. The Wall symbolizes the transition from the past to the present which

is made clear throughout the film. It is a symbol of the war. It is always

onscreen proving that it is constantly a part of life in Berlin. The library

and the circus are mirrors of life, the former, of permanent aspects, the

latter, of temporary ones. The library is a symbol of history, including

collected memory and the knowledge of mankind that is permanent all the

time. The circus is a symbol of identity, human relations and belonging to a

place, that are the positive aspects of life, and it shows the temporariness

of these concepts. A detailed analysis of each of these spaces will follow.

Berlin

In ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, the first thing that is framed is the city.

The film cannot be shot somewhere else, it is setting based. Wenders says, "The

thing I wished for and saw flashing was a film in and about

Berlin. A

film that might convey something of the history of the city since 1945,"

(1991: 73). Wenders analyzes the city of Berlin as a Berliner who look at

the city from the outside but still as an insider: “All the other films I

made in

Germany

were about trying to get out of the place. This time I still had the point

of view of an outsider, but I tried to look in,”

(Fusco, 1988: 14). After Germany, Wenders made films in the United States

and this is his first film back in his country as someone who can look in

from the outside, like the angels. The director has a poetic description for

Berlin and his film (1991: 74-76):

And so I have 'BERLIN'

representing 'THE WORLD'.

I know of no place with a stronger claim.

Berlin is 'an historical site of truth'.

...

Berlin is divided like our world,

like our time,

like men and women,

young and old,

rich and poor,

like all our experience.

...It's more a SITE than a CITY.

...

My story isn’t about Berlin

because it is set there,

but because it couldn’t be set anywhere else.

The name of the film will be:

THE SKY OVER BERLIN

because the sky is maybe the only thing

that unites these two cities,

...

with a common past

but not necessarily a shared future.

And what of the present?

That is the subject of the film:

THE SKY OVER BERLIN

OVER BERLIN?,

in, with, for, about Berlin . . .

What should such a film

'discuss', 'examine', 'depict', or 'touch on'?

...

ONE story about DIVISION

...

In the film of course it’s not HISTORY

but A story, though of course

a STORY may contain HISTORY,

images and traces of past history.

...

"Wenders'

‘symphony

of a great city’

is conducted from on high," (Kolker and Beicken, 1993: 144). The film

starts with views of Berlin from the air with "the aerial point of view of

the angel" (ehrlich, 1991: 242), as a

representative of urban space scale. "[T]he

camera takes angel flight, gliding through the Berlin cityscape,"

(Kolker and Beicken, 1993: 143). In the second set of images, the camera

zooms in a “nineteenth-century worker housing” (Harvey, 1990: 315),

which can be considered as a representative of building scale. Robert

Phillip Kolker and Peter Beicken emphasize “an ‘objective’ observation of

an urbanity strained by the conflicting and violent demands of the middle

and working class,” (1993: 143). As the third set of images, the camera

enters the housing through a window showing the rooms of apartments, as a

representative of interior space scale. Wenders’ camera is “swooping from

great heights, entering apartment rooms, wandering and drifting through the

city, making divine cinema," (Kolker and Beicken, 1993: 144). These

lonely private apartment rooms are the first representatives, in the film,

of the divided spaces of Berlin.

In ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, Berlin is represented both as a very

specific city and as one of the many metropolises. Wenders says “Berlin,

the divided city of course, was just another metaphor, like the angels

themselves. Berlin seems to be a city that well represents not only Germany,

but also our civilization. In a way, Berlin really represents the world,”

(Fusco, 1988: 16). It is framed as a cosmopolitan city of 1987 with

people belonging to different nations and speaking (and thinking in)

different languages. Berliners are not only Germans (as Hitler wished) but

also people from all over the world. Les Caltvedt says, “The city is also

home (or “home”) to foreigners; ... she

[Marion]

feels most at home because she is a foreigner”

in Berlin (1992: 122). Linda Ehrlich says (1991: 244):

‘Wings of Desire’ reaches toward universality within the specific

geographical and historical framework of postwar

Berlin.

Characters speak German, French, English, Hebrew, Japanese, Turkish –

sometimes without subtitles – which places the viewer right in the middle of

a cosmopolitan urban setting where no one in real life offers subtitles.

In the film, the space of the city of Berlin can be seen as divided into a

foreground and a background. In the foreground, one may see the divided

postwar city of 1987 and in the background, there is the city of ruins from

1945. Two visions are superimposed in the film; the living, therefore

changing Berlin-of-the-80s and the frozen image of

Berlin-of-the-40s that is constant in all sequences, “an idea of

juxtaposing and superimposing today’s Berlin and the capital of the Reich,

‘double images’ in time and space” (Wenders, 1991: 77). Contemporary

Berlin is in the consciousness while the frozen image as the result of the

break in 1945 is in the subconscious of the actual city. Wenders says, "Behind

the city of today, in its interstice or above it, as though frozen in time,

are the ruins, the burned chimneystacks and facades of the devastated city,

only dimly visible sometimes, but always there in the background,"

(1991: 79-80). Through Wenders’ camera “the former capital” (Paris:

1993, 238) runs after the present. “[T]he

hi(story) that elsewhere in the country is suppressed or denied is

physically and emotionally present here,"

(Wenders, 1991: 74). Time passes but Berlin-of-the-40s persists. He says "this

yesterday is still present everywhere, as a 'parallel world'" (Wenders,

1991: 80) which is visible to the angels in the film as well as to

Berliners. Peter Green says (1988: 128):

Wenders’

Berlin,

destroyed by the war, ravaged by subsequent reconstruction and torn apart by

the Wall, which has turned the very heart of the city into a peripheral

zone, is a picture of a waste land littered with the ruins of the past and

the cold concrete of postwar developments. Here Wenders resumes his search

for time and place. Berlin functions both as a backdrop against which the

other layers of his film are set, and as the living tissue through which

Curt Bois wanders, a Homeric commentator in pursuit of the city’s lost

identity.

Wenders finds flashback unsafe for the temporal and spatial unity of a film

(Lewis, 1984: 51). For this reason, he uses two ways, other than flashback,

to go back in time and visualize Berlin-of-the-40s in ‘Der Himmel

über Berlin’. As the first way, a film that represents 1945 is shot, and as

the second, angels who have no temporal limitations jump from 1987 to 1945.

In the film, “an American crew, including Peter Falk, makes a film about

wartime

Berlin,”

(Caltvedt, 1992: 122). In the “film-within-the-film,” (Paneth, 1988:

2) there are soldiers in Nazi uniforms and Falk’s ‘extra people’, the

Jewish. By using the images of a film set representing the Nazi period that

is a ruined “multi-leveled air raid shelter” (Ehrlich, 1991: 244)

with a hole in the middle of the slab, Wenders does not flash but goes back

to Berlin-of-40s. On the other hand, he uses “documentary material and

film in film to create shifts in time” (Green, 1988: 129). Through “old

newsreel footage of wartorn

Berlin and

Nazism,”

(Paneth, 1988: 2), “the past dissolves into the present, and back again,”

(Ehrlich, 1991: 245). Kolker and Beicken describe one of the “street

scenes that conjure up images of war-time destruction” (Harvey, 1990:

316) as follows:

This sequence follows Cassiel’s car ride through

Berlin,

during which old footage of the last months of the war and the rubble of

bombing raids... Cassiel sees past and present, and in voice-over he

meditates upon history and the German spirit, its lack of individuality and

sense of spiritual community

(1993: 153).

|

|

Figure

8

‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ |

|

In Wenders’

film, specific spaces that are represented as parts of the city help

“the exciting rediscovery of

Berlin”

(Paris: 1993, 238). These spaces which are represented as fragments within

the framework of Berlin are the Potsdamer Platz – the old city center,

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Victoria’s statue, and the outdoor snack

wagons that stand in the middle of the ruined parts of the city (figure 8),

the caravan, the bar and the laundromat. “After years of filming on the

road” (Fusco, 1988: 14), Wenders cannot eliminate the streets of

Berlin as well. The viewer finds himself experiencing space in moving

vehicles such as cars, subway trains, ambulances or “on the upper level

of an empty double-decker bus" (Ehrlich, 1991: 245). Caltvedt says

(1992:124):

In ‘Wings’,

it seems that the street further distinguishes between the “blessed”

(angels, former angels, aerialists, and children) and the others. Peter Falk

enjoys Berlin the most on the street... The angel Damiel begins his new

human life on the street. ... The street – covered by the sky – is the

primeval shelter where people can encounter one another.

In Berlin, humans live on the street, whereas the angels are free from

vertical and horizontal boundaries, from the limitations of space and time.

"[A]

transcendent, 'timeless' city for the actual Berlin of today"

(Wenders, 1991: 81) is present for the angels. When the angel, Damiel,

became human, he 'traveled' from the angels'

Berlin

to the humans'

Berlin,

the former being a three-dimensional totality and the latter a lonely,

hopeless labyrinth, the collage of worlds rejecting one another. The angel,

in this transformation, is represented as a transition element from the

imaginary to the real, from the permanent to the temporary, from the world

as one to the world in pieces, from eternity to today, from anywhere to

here, from a black and white world to a colored one.

Wenders’ Berlin is symbolic; he interprets Berlin as a symbolic

site: “No other city is to such an extent a symbol, a place of survival.

It is a site, more than a city,” (Paneth, 1988: 2). “Combining

allegory and document, striking cinematography and multilayered sound,

Wenders offers a lyrical reflection on German history and culture that

transforms Berlin into a rich symbolic landscape,” (Fusco, 1988: 14). “The

film explores this wideanging significance:

Berlin as a

symbol of the post-World War II world order, of borders, no-man’s land,

desire and, most of all, of German history and Nazism,”

(Paneth, 1988: 2).

Moreover, Wenders shifts space to a social level in ‘Der Himmel

über Berlin’. He focuses on the social aspect of the city and architecture

and their place in people’s lives instead of their physical aspects. The

city is a part of the chaotic social life and is the reflection of society.

He visualizes his perception of the society by using the city as a social

tool. He says, “I didn’t want just to make a film about the place,

Berlin. What I wanted to make was a film about people – people here in

Berlin – that considered the one perennial question: how to live?”

(1991: 74). The film not only shows the two superimposed visions of Berlin,

but also reflects the psychology of its citizens. For him, the city and its

citizens compose an inseparable whole, transform one another; the stories of

the citizens form the history of the city. The city is treated like a living

organism which gets shape with the social life in it.

The wall

The Berlin Wall is a continuous horizontal concrete structure, lying

between West Berlin and East Berlin, constructed in August 1961 to prevent

transition between the two. There exists “the no man’s land between two

lines of the

Berlin

Wall, patrolled by soldiers”

(Harvey, 1990: 319). The inner faces of the Wall are gray in color, while

the face on the west side has colorful graffiti of human faces in big

scales. The eastern face is never onscreen. The Wall is not too high, but it

is impossible to see the other side. It was demolished in 1989, two years

after the production of the film. Ehrlich says “the

Berlin Wall

which forms another leitmotif”

perpetually repeats itself in the film (1991: 243). The Wall can be seen as

an object, as a divider, as a barrier, as a landmark, as a frame and as a

symbol in ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’.

The Wall as an object: The Wall “which the film continually

runs up against” (Paneth, 1988: 2) is an architectonic element within

the city. It is always with you in Berlin. It is in the foreground.

The Wall as a divider: First, the Berlin Wall was a boundary

between two pieces of a big city. Now it is between two different cities.

The Wall as a barrier: The transparency of the Wall for angels

emphasizes its solidity for humans. The Wall “has never previously been a

barrier to” the angels (Wenders, 1991: 82). Wenders says "with angels

you could do anything, there were connections all over the place, you can go

anywhere. You could cross the Wall, pass through windows into people’s

houses," (1991: 109); “they can slip through the Wall,” (Green,

1988: 129). But the Wall means neither transparency nor continuity for

humans. They cannot pass it, cannot see the other side. It is an element of

division and separation.

The Wall as a landmark: Wenders says, “The Wall has been there

for such a short period of time compared to the time they

[angels]

have been there. They are not impressed,”

(Fusco, 1988: 16). But for humans, the Wall is a landmark. “‘It is

impossible to get lost in

Berlin,’

someone says, because you can always find the wall’,”

(Harvey, 1990: 316).

The Wall as a frame: The aim of the Wall was to divide Berlin

into two but its construction broke the city not merely into two, but into

many pieces. Today the Wall does not exist, but its essence lies within the

fragmented city.

The Wall as a symbol: The Wall is a symbol and a reminder of the

war, and a part of the memory of the 1940s. It symbolizes the transition

from the past to the present. It is the three-dimensional representation of

the city in pieces. Harvey says (1990: 316):

The distinctive organization of space and time is, moreover, seen as the

framework within which individual identities are forged. The image of

divided spaces is particularly powerful, and they are superimposed upon each

other in the fashion of montage and collage. The

Berlin Wall

is one such divide, and it is again and again evoked as a symbol of

overarching division. Is this where space now ends?

The library

|

|

Figure

9

‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ |

|

In the film, the library, Berlin Public Library (Kolker and Beicken, 1993:

142), is represented in interior space scale. It is a mystical space (music,

murmuring) with huge slander white columns, high ceilings and an atrium with

a large staircase in the middle that unites the space within the library (figure

9).

It is wide and spacious. A part of the roof is made of glass, and there are

balcony-like projections of the gallery. Light comes from big circular

sources on the ceiling. Even in this single space, humans are alone, each

sitting and reading at a table with its own lamp. It is peaceful and calm,

mysterious and innocent. Everything is in silence except the collected

knowledge which is the source of evaluation. Wenders describes the space as

follows (Paneth, 1988: 6):

I thought this is a heavenly place, a library, ... it’s really a wonderful

place, with a lot of light, and built with a lot of respect for reading and

books, and also so peaceful and quiet. There is also the whole memory and

knowledge of mankind united there.

Books are the documents of history and the library is the home of books. It

is the disorder of the orderly. Formally it is in order, but contextually it

is completely in disorder. It is the chaotic crowd of pieces of collected

memory and it helps to picture the whole history by connecting these

pieces. It is a timeless space belonging to history. Paneth says “I

thought the handwriting at the beginning and the end and the library were

wonderful gestures toward the written word,” (1988: 6). The library, as

Kolker and Beicken describe, is "the archive of human memory" (1993:

149). It is for reading, for remembering, for thinking, for questioning, for

searching, for learning, for understanding and for knowing. It is the museum

of the knowledge of the past. Caltvedt refers to this “otherworldly space”

as follows (1992: 124):

Another “felicitous space” is the state library, which houses angels, a

man called Homer, and anonymous patrons. The soundtrack, the angels, the

postures of the readers all suggest sacred space. ... The library contains

in spirit the whole universe, and guides the viewer initiate to the written

word (in the beginning was the Word), “heavenly” music, a small flock of

angels who hang around in the stacks, humankind’s photo album (August

Sanders’s anthropological collection, Citizens of the Twentieth Century) and

a whole collection of globes.

|

|

Figure 10

‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ |

|

The

story-teller is related to the library in the film. Wenders says “we had

Homer living in a library,” (1991: 112); “he uses the library to try

and recuperate a proper sense of the history of this distinctive place

called

Berlin,”

(Harvey, 1990: 317). But the real inhabitants of the library are the

angels (figure 10). It is the “headquarters

for the celestial beings” (Paris, 1993: 238). Wenders thinks of the

library as “a place in the city where the angels would live, would be at

home,” (Paneth, 1988: 6). “In their nocturnal haunt in the

depopulated library they appear drained in the monochromatic light, trapped

in an exquisitely isolated perfection,” (Ehrlich, 1991: 245). Kolker and

Beicken say that "it is a brilliant conceit to present the library as the

gathering place of the angels," (1993: 149) maybe because it is really a

timeless space. Are there really so many angels in a library?

The

circus

|

|

Figure 11

‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ |

|

In ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, the circus is represented first from the

outside framed by the ruins of the city in building scale. Green claims “through

a gateway one suddenly catches a magical glimpse of an elephant and a circus

in the heart of the city,” (1988: 129). Through this frame-within-frame

the circus is perceived as a big circular pavilion made out of tent canvas.

It has a column in the center which is raised till the top point of the

ceiling; the circus is a juxtaposition of a cone above a cylinder. Then the

camera goes in and records the circus in interior space scale. It is a large

single space. It is round and has stepped seats all around which avoid

hierarchy (where it differs from life). From the center to the periphery,

the seats rise. It has a circular stage in the center where the whole

performance takes place. As the trapezian girl swings (the camera swings too

but more slowly), the viewer perceives the three-dimentionality of the space

in the circus. Marion’s rehearsal is the first colored shot in the film (figure

11).

Wenders says “since the whole film also deals with children, I

thought of a circus,” (Fusco, 1988: 15). "A circus is a privileged

spot because of the presence of children, and with all the waste ground in

Berlin there is always a circus there," (Wenders, 1991: 111). The circus

is a space where the show represents situations belonging to life such as

difficulty, comedy, magic and danger. It is a mirror of the positive

aspects of life. Nothing goes wrong there. It is for fun and

entertainment. It is the space for the imaginary, the instant, the temporary

and the extraordinary. It is an image of things belonging to or concerning

life, whereas the viewer’s relation with real life is broken in the circus,

as it is the case while watching a film.

The circus arrives at a place but it always leaves as well. Because of

its mobile Nomadic life it is never ever-lasting; it is always temporary.

It is a guest in the city, not a part of it. It does not belong anywhere.

Even the material of the round tent is not durable. Mentioning the circular

trace of the circus on the ground Ehrlich says “’Wings of Desire’ is full

of both abstract and concrete circular images: The circus ring, finally

reduced to a circle of sand in a field when the bankrupt circus is forced to

pull up stakes,” (1991: 245). “The circus tent is, while the circus

survives, the felicitous space of

Marion’s

art...

[T]he

angel Damiel returns to the circle of sawdust that remains; the power of the

tent seems to linger,”

(Caltvedt, 1992: 124). “The circus ... starts as a place of respite for

the angels, a counterbalance to the dark abyss of the past, but becomes the

scene of Damiel’s transfixion and transition,” (Kolker and Beicken,

1993: 155).

“How can some sense of identity be forged and sustained in such a world?

Two spaces assume a peculiar significance in this regard. The library – a

repository of historical knowledge and collective memory – is a space into

which many are evidently drawn (even angels seem to take their rest there),”

(Harvey, 1990: 317). “But there is a second site where a fragile sense of

identity prevails. The circus, a spectacle held together within the enclosed

space of a tent, offers a venue of special interaction within which some

kind of human relating can go on,” (Harvey, 1990: 318). Hope

still exists in the circus. The feeling of space, time, identity and place

are present. The circus is the result of the nature of its own life. It is a

timeless and international space with no style. But any circus is “a

soon-to-be-disbanding” one (Paris, 1993: 238). Migration never ends and

hope never stays.

|

|

Figure 12

‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ |

|

It can be

stated that Wenders' films make the viewer think about specific spaces such

as ‘city’, ‘library’ and ‘wall’. Wenders makes the viewer think about the

typologies of spaces he represents. He examines their meanings. He

thinks of the essence and the character of these spaces. Representing a

different approach to specific spaces, Wenders’ analysis show architects a

way in understanding particular spaces (figure 12).

As in Wenders’ cinema, films in which space is in the foreground suggest

different ways to perceive, experience and interpret the represented

architectural space. This can expand the perspective of the viewer including

the architect. (De/re)contextualization gives cinema the opportunity

to approach to space through different ways. Architecture is contextual and

is (de/re)contextualized in cinema by using framing and montage. As the

result of (de/re)contextualization, cinema focuses on aspects of space that

are hard to be perceived while looking at the whole within a context and

creates secondary meanings. Architects may learn a lot about architectural

space through its representation in cinema.

Citation

Bowman, Barbara, 1992. “Introduction: Space in Classic American Film,”

Master Space: Film Images of Capra, Lubitsch, Sternberg, and Wyler,

Greenwood Press, New York, Westport, Connecticut, London, pp. 1-11.

Caltvedt, Les, 1992. “Berlin Poetry: Archaic Cultural Patterns in Wenders’

‘Wings of Desire’,” Literature / Film Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 2, pp.

121-126.

Carroll, Noel E, 1988. “The Cinematic Image,” Mystifying Movies: Fads and

Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory, Columbia University Press, New

York, pp. 89-146.

Ehrlich, Linda C, 1991. “Meditations on Wim Wenders’s ‘Wings of Desire’,”

Literature / Film Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 242-246.

Fusco, Coco, 1988. “Angels, History and Poetic Fantasy: An Interview with

Wim Wenders,” Cineaste, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 14-17.

Green, Peter, 1988. “Germans Abroad,” Sight and Sound, vol. 57, no.

2, pp. 126-130.

Harvey, David, 1990. "Time and Space in the Postmodern Cinema," The

Condition of Postmodernity - An Inquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change,

Basil Blackwell Ltd., Massachusetts, pp. 308-323.

Kolker, Robert Phillip, and Peter Beicken, 1993. The Films of Wim Wenders:

Cinema as Vision and Desire, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lewis, Brent, 1984. “Wim Wenders ile Söyleþi: Paris, Texas,” Geliþim

Sinema, November, vol. 2, pp. 50-51.

Metcalf, Greg, 1993. “The Other Kind of Movie Trailer: Mobile Homes in

American Movies,” The Material World in American Popular film, Vol. 3

of Beyond the Stars: Studies in American Popular Film, eds. Paul

Loukides and Linda K. Fuller, Bowling Green State University Popular Press,

?, pp. 229-242.

O’Herlihy, Lorcan, 1994. “Architecture and Film,” Architectural Design,

November - December, vol. 64, no. 11/12, pp. 90-91.

Paneth, Ira, 1988. “Wim and His Wings,” Film Quarterly, Fall, vol.

XLII, no. 1, pp. 2-8.

Paris, James Reid, 1993. Classic Foreign Films from 1960 to Today.

Citadel Press, Paris, New York.

Sobchack, Vivian, 1987. “The Deflation and Inflation of Space,” and “The

Collapse and Conflation of Time,” Screening Space: The American Science

Fiction Film, Ungar, New York, pp. 255-281.

Wenders, Wim, 1991. "An Attemped Description of an Indescribed Film," and

“Wings of Desire," The Logic of Images: Essays and Conversations,

Faber and Faber, London, Boston, pp. 73-83, 109-113.

Figure

references

Figure

1.

Paris, Classic Foreign Films, 160.

Figure 2.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders , 3.

Figure 3.

Videosinema,

85/4, 39.

Figure 4.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 130.

Figure 5.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 37.

Figure 6.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 127.

Figure 7.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 69.

Figure 8.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 157.

Figure 9.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 149.

Figure 10.

Paris, Classic Foreign Films, 237.

Figure 11.

Sight and Sound,

87/3, 169.

Figure 12.

Kolker and Beicken, The Films of Wim Wenders, 139.

Film

credits

’Der Himmel über Berlin’ (‘Wings of Desire’)

(B&W, colour, 35 mm, 127’)

Director: Wim Wenders

Assistant directors: Claire Denis, Knut Winkler, Carola Hochgraf

Screenplay: Wim Wenders, Peter Handke

Cinematographer: Henri Alekan (black and white, Eastman-color)

Assistant cinematographers: Louis Cochet, Agnes Godard, Achim Poulheim,

Peter Ch. Arnold, Martin Kukula, Frank Blasberg, Peter Braatz, Klemens

Becker, Klaus Krieger

Art director: Heide Lüdi

Editing: Peter Przygodda

Assistant editors: Anne Schnee, Leni Savietto-Pütz

Music: Jüngen Knieper, Laurent Petitgand, Laurie Anderson, Crime and the

City Solution, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Sprung aus den Wolken,

Tuxedomoon, Minimal Compact

Cast: Bruno Ganz, Solveig Dommartin, Otto Sander, Curt Bois, Peter Falk

Producers: Wim Wenders, Anatole Dauman

Associate producer: Pascale Dauman

Production company: Road Movies, Berlin; Argos Films, Paris; Westdeutscher

Rundfunk, Cologne

Premiered: 17 May 1987

|

|

|

feedback |

|

Vol. 9, No. 1

November 2004 |