| On

the Interpretation of Architecture Applied Interpretation Vol. 13, No. 1, May 2009 |

|||

| ___Andrzej

Piotrowski Minneapolis |

On Interpretations: A Case of Unselfconscious Representation |

|

Interpretations of buildings

are as prevalent as they mislead the general public about the conceptual

constitution and functioning of architecture. They divert attention away

from inherently architectural characteristics of built environments and

towards self-serving systems of narratives. While an empirical study of

a building’s physical or social performance follows the methodology of civil

engineering or the social sciences, an interpretation of so-called meanings

seems to add a different, unverifiable, dimension to that knowledge. In

common perception it is exactly the added narrative that transforms a physical

building into a piece of architecture – a structure with a verbal sense

of conceptual integrity. In this way interpretations draw an artificial

distinction between meaningful and meaningless forms. One could argue that

the discipline of architecture, and especially the history of architecture,

establishes its own field only as far as it adds symbolic interpretations

to methodologies borrowed from scientific or empirical fields. Practicing

architects follow the same pattern when they promote their expertise as

an ingenious combination of arts and sciences. They project creativity in

shaping artistic intentions but also guarantee rigor and competence in designers’

ability to solve problems. Artistic expression seems to be the primary domain

of conceptual thinking thou because each time a designer uses the expertise

of a structural engineer or consultant in fields such as acoustics, s/he

tacitly acknowledges that architects depend on external and specialized

knowledge. This polarized model of thinking is popular because it is deeply rooted in the epistemological assumptions that shaped Western knowledge. It is grounded in René Descartes’ dichotomy of matter and spirit, which conveniently separated the certainty of so-called physical facts from the uncertainty of the processes of sense-making. Maybe the most important, however, is the legacy of the nineteenth century, the period when the polarity of the emotional will and the rational mind – the founding principle of the Romantic Movement – defined the relationship between the arts and the industrial revolution. That way of thinking was grounded in the discourses of philosophers such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel who defined art as a mere object of contemplation perceivable best when abstracted from real life, devoid of practical usefulness, depoliticized, and placed in the newly invented space of a museum (Bennett 1995, p. 92). Theoretical aspects of coding meanings were refined by semioticians such as Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce who separated the signifier, the sensory pattern created by what a person perceives, from the signified, the meaning that the mental pattern elicits (Saussure 1916, pp. 111-22). These epistemological divisions created an impression that the meaningful world is the reality of well-formed signs which depend on and thus can be studied with the help of language.[1] Architectural discourses preceded and followed these theoretical ideas. John Ruskin and Alexander James Beresford Hope used the issue of the national style as a vehicle to elaborate on the function of narratives in shaping the correct understanding of architecture.[2] Others, Gottfried Semper, for example, studied the issue of material articulation and identified the skin of a building as the surface of symbolic inscriptions (Semper 1989). Altogether designers and theoreticians of the nineteenth century produced a model in which architecture consisted of a meaningless material frame which physically supported the embellishment containing meaningful signs. While the principles of physics integrated the frame, a carefully crafted symbolic narrative provided consistency in the system of signs the building manifested. The traditional history of architecture is steeped in this epistemological model and has used it to filter buildings across time and cultural divisions. It has operated in this way when scholars assumed that a meaningful building consisted of two complementary sets of attributes: (1) those that resulted from deterministic decisions – reflecting necessary or unavoidable factors of climate, technology, or economy – and (2) those resulting from intentional decisions concerning artistic or symbolic expression. This dichotomy of necessity and will has been instrumental in the colonization of others because its seeming consistency hides processes which eliminate other ways of thinking. Any understanding of reality that did not subscribe to the Western model was deemed inconsistent and/or unscientific.[3] Only the Western episteme had the power to project a totalizing vision in which both the principles of physics and the realm of meanings appeared to be guided by well-formed rules and transcendental principles. By epistemological extension the masters of material technology projected confidence in the universal applicability of their systems of classifications and interpretations. In this way the colonial powers imposed their system of hermeneutics, evolutionary continuities of styles, and the taxonomy of historical periods on the whole world.[4] Unfortunately many contemporary theories retained elements of the same traditional attitude. Generally speaking, I consider scholarly studies to be nontraditional if they admit that not only collected information but first of all the criteria defining truth and relevance of what one knows have been subject to political and economic forces. Frequently grounded in critical theories, these kinds of discourses generally follow Michel Foucault’s assertion that power “produces reality,” (Foucault 1977, p. 194). These kinds of discourses have disrupted pre-existing systems of interpretations because they focus attention on the epistemological constitution of the knowledge itself. Yet some of these scholarly strategies are still grounded in the quintessentially nineteenth century (primarily Marxist) notions of social and political determinism when they tacitly assume that power functions only when it is conscious of its own objectives and actions. True in the case of ideologies, which verbally articulate their political programs, this belief is more questionable when one considers how power relates to non-verbal constructs, like those of architecture. A popular way to eliminate this doubt is to assume that power produces reality because any order is inseparable from and thus is controlled by language. For example, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, a renowned cultural theorist, says that "we know no world that is not organized as a language, we operate with no other consciousness but one structured as a language" (Spivak 1987, pp. 77-8). Such a belief follows directly the nineteenth century scholarly tradition. This kind of assumption still positions the systems of symbolic interpretations in the center of the discipline of architecture. I wish to assert that the task of interpreting architectural meanings is epistemologically misguided if it assumes that a well-designed building communicates intentionally formed messages or that the system of signs the building supposedly embodies is stagnant or universal like the so-called natural symbols. Only a structure that was intended as an explicit symbol of a self-conscious power may subscribe to such a reductive formula and even that is only true for those who agree to think like the authority which has imposed these meanings. Fortunately the great majority of buildings all over the world and across time manifest much more complex processes of sense-making. I believe that buildings generally do not communicate but represent, an essential distinction if one wants to study the specificity of the discipline of architecture. A built structure does not convey coded messages but rather enhances a particular way of thinking. Unlike verbal communication, this kind of process does not aspire to achieve the univocal clarity of the transmitted content, but rather, as a mode of representation, it gives form to unselfconscious concerns or desires. From the time the initial design ideas are proposed until the time the built form is used, architecture primarily engages nascent thoughts. Although the design process – the transition from the ambiguity of initial visions to the legal certainty of a construction document – seems to exemplify the emergence of concepts most explicitly, I believe that this process continues beyond the time of physical construction. The building’s program is never stagnant. As Andrew Benjamin suggests, “the building becomes a plural site of which the traditional function is but a single trope because of the recognition that contemporaneous with this, as the building’s logic, is the politics of that building”. (Benjamin 2000, p. 125) Only the pragmatic aspects of architecture can be analyzed in an unequivocal or quantifiable way. How an inhabited structure orders spatial and visual phenomena, how it uses materials to organize experiences, how it implies relationships among its users, how it prompts who controls its symbolic features, or how its form resembles other places or concepts, all these attributes operate on the level of a nascent thought. Rather than shaping rational understanding, buildings engage attention; they prompt an attitude rather than form a correct knowledge or interpretation. And it is in this way that physical building functions like a design sketch and invites directed but open-ended insights. Because buildings do not impose concepts of reality but make them thinkable many ideologies may coexist and be in symbolic dialogue with one another within the same physical space.[5] Buildings represent these frequently conflicted worldviews because the program of a lived space never achieves the self-conscious clarity of an ideological program. Symbolic encounters and interactions accumulated within or triggered by architecture cannot be totally controlled. This is why, across history, material structures gave form to ideas or attitudes that were too nascent or too complex for words. More importantly than communicating well-formed symbolic meanings, buildings have facilitated processes of thought formation and cultural negotiations. |

||

Figure 1  Figure 2 |

In order to exemplify these

processes of thought formation and cultural negotiations I would like to

focus on one case, the Holy Trinity Chapel (Kaplica Świętej Trójcy)

in Lublin, Poland.[6]

As Figure 1 shows, it is a part of what used to be a minor royal castle

in eastern Poland. The castle has now been radically altered and transformed

into a regional museum but the chapel has remained intact. So far, not much

attention has been devoted to the study of the physical structure itself.[7]

The fact that those who have explored its decorations see it as a curious

mixture of styles and influences makes it relevant for my argument. In those

kinds of studies this royal commission appears to be stylistically confused,

provincial in its intent and execution. This makes it a perfect example,

however, of how the traditional scholarship filters out buildings across

time and cultural divisions. Deeming a piece of art or architecture as “provincial”

practically implies that such an artifact lacks certain features characteristic

of so-called high culture, that is, its design is not sufficiently aligned

with the stylistic principles of the ideology that dominated that region

or nation. Provincial phenomena are usually seen as synonymous with the

peripheries of political and intellectual influence. Location alone is not

sufficient thou to dismiss a building in this way. Even a structure built

in a cultural center may be deemed inferior if its designers seem to have

misunderstood proper rules, lacked technical expertise, or were supposedly

incapable to intellectually synthesize issues within the dominant system

of expression. Such examples are excluded from the traditional history surveys

of world architecture. Canons of monuments are grounded in the epistemological

assumption that, throughout history and across the world, only intellectual

elites produced architecture of superior conceptual integrity – buildings

representing sophisticated consistency of meanings and material means of

expression. Not surprisingly the locations of those monuments coincide with

historical centers of political and/or ideological power. Such an assumption

dismisses not only other buildings but also, and more importantly, the whole

spectrum of architectural thought that functioned outside of the dominant

structures of control. The Holy Trinity Chapel is such an insufficiently explored example of architecture. Although the first record referring to the chapel comes from 1326, the date of its completion is not known. Some historians believe that the final phase of the building’s construction coincided with the time when Jagiełło politically united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[8] In 1386, Ladislaus (the Latin name given to him at the Christian baptism) Jogaila was crowned king of Poland as Władysław Jagiełło and thus established a new dynasty and a personal union between the two states. The Holy Trinity Chapel is a small structure consisting of two interior volumes stacked vertically, the main hall above and the crypt below. If judged according to traditional taxonomies the chapel indeed seems to represent a case of split symbolic personality, a space in which Western and Eastern concepts of religious space create a tension, if not a deep conflict. While the structural solution and spatial articulation are Gothic, the interior decorations are Russian-Byzantine. Anna Rόżycka-Bryzek, an expert on Russian-Byzantine paintings who had studied the chapel extensively concluded that while the symbolic program in the Holy Trinity Chapel is of Byzantine origin its proper execution was compromised by its incompatibility with the Gothic building (Rόżycka-Bryzek 2000, pp. 30 and 35).[9] The paintings were commissioned by Władysław Jagiełło and finished in 1418. Figure 2 shows the multiplicity of colors and the density of the figurative compositions in the relatively small space. They form a tapestry of religious iconography that totally surrounds the believer. This effect of visual immersion is enhanced by its stark contrast with the building’s austere and technically efficient brick exterior depicted in Figure 1. Similarly to many Byzantine and post-Byzantine interiors located in Turkey, Greece, the Balkans or Russia, in Lublin, a person's vision and imagination become wrapped in the world of icons. In the Holy Trinity Chapel, figurative compositions cover all the walls, floating against the bluish background. Lines painted on vertical surfaces create areas for individual images and they only loosely relate to Gothic features such as the shapes of the walls or the placement of windows and doors. The multiplicity and arrangement of paintings defy the physicality of the walls. At the same time, as Figure 2 shows, the Gothic structure in the chapel is strongly articulated too. Elements such as ribs clearly reveal the flow of forces. After 1054, the beginning of the Great Schism between the Christian East and West, the treatment of a church interior was among the most explicit indicators of ideological affiliation. The Byzantine Empire and its heirs used imagery and light phenomena to defy the corporeal reality of their church interiors.[10] In contrast, especially with the advance of Scholasticism in philosophy and the Gothic style in architecture, the builders of Western Europe emphasized material structure to represent its rational perfection as the recreation of the divine order on Earth.[11] In Lublin, the two kinds of symbolic expression that separated the Christian East and West coexist. They are not just physically co-present; they are in a difficult dialogue. The structural ribs, for example, are covered with colorful patterns. Such added appearance is not meant to diminish their materiality or blend them with the tapestry of images. They remain strongly discernable and only acquire those visual characteristics that allow them to function like lines painted on walls. In effect, the ribs organize the vaults just like the flat borders divide the vertical surfaces. Unlike Anna Rόżycka-Bryzek I wish to suggest that this interior has not resulted from the unfortunate and unavoidable conflict but rather can be seen as a representational experiment intended to test a hybrid concept of religious space. Once approached in this way, other features of the chapel gain relevance. In Lublin, agreements between Western and Eastern symbolic practices seem as meaningful as the articulation of their differences. Gothic and Byzantine legacies, if considered not as sets of rules but as ways of thinking, create the strongest tension in the center of the chapel, for example. |

|

Figure 3  Figure 4 |

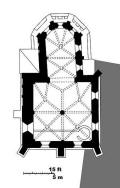

While

Byzantine churches were primarily composed around the central naos and its

vertical axis, Gothic churches emphasized a horizontal procession towards

the main alter. These two layouts were reinforced by different distribution

of daylight. Figure 3, a plan of the chapel, shows that in this small structure

the presbytery implies the horizontal directionality of the space. The footprint

of the main hall is square and thus similar to Byzantine and post-Byzantine

churches. As Robert Kungel’s studies have shown, in the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries, on the western outskirts of Lithuania, the Gothic style was also

used in Orthodox churches. Often their size and layout were similar to that

of the Holy Trinity Chapel, with one exception: their central space was

structured by four columns and thus the very center of the church remained

empty (Kungel 2000, pp. 37-54). Four columns in the center are characteristic

of the Russian Orthodox church model where the central space is taller and

infused with light coming through windows of a large lantern above, a solution

reminiscent of the light phenomena seen in Byzantine structures. It was

that experiential quality of light captured at the top of the church interior

that provided the nonfigurative representation of divinity. In contrast, figure 4 shows that in the Holy Trinity Chapel the central space is occupied by the most material and technically explicit of building elements – a column, which reveals how human ingenuity transferred forces of gravity from the ceiling to the ground. This representational shift redirects thoughts away from the East Orthodox vertical progression of symbolic hierarchy and towards the Western symbolic procession to the altar.[12] Thus, in the center of this apparently Russian-Byzantine visual space of representation, an ephemeral phenomenon is replaced by a material statement of technology. Yet, painted figures above the column recall in their character and position those that would be depicted on a Byzantine dome. This is a radical juxtaposition of two modalities of religious thought; a set of transpositions and reversals. The differences between these two ways of constituting religious symbolism were so profound and politically charged that according to strict architectural principles an interior like this should have never been completed. But it does exist. The Holy Trinity Chapel is not a compromised or imperfect space of representation. Nor was the juxtaposition of the Byzantine and Latin ways of symbolic ordering meant to dominate or subvert the principles of the other belief. The chapel is a material manifestation of thought seeking new ways to question the schismatic divisions within European Christianity. I believe that it is not a coincidence that the paintings in the chapel were completed only 21 years before the Union of Florence (1439), the most successful attempt to reconcile Constantinople and Rome since 1054. This place of worship reflects a way of thinking that is not ignorant of differences but rather refuses to follow centuries-old patterns of constructing ideological conflict for political reasons. All relevant principles of religious thought are acknowledged, but none of them is allowed to dominate the whole spectrum of experiences. This space of representation does not manifest a new religious program, though. Despite renewed political efforts to reconcile Eastern and Western Christianity, no architectural pattern of this new kind could exist. This building provided an opportunity to explore difficult issues of its time. It could not subscribe to a well-formed symbolic system. It could, however, manifest a desire to bridge political and ideological divisions or to test non-dominant coexistence of different worldviews. The personal union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was an effort to build an alliance between people of different languages, religious beliefs, and political affiliations. While the power structures of the Kingdom of Poland were already well-integrated with those of the Western Christianity, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was as large as it was culturally diverse. Even long after its southern parts – the Kievan Rus with the Duchy of Halicz-Vladimir – pledged their religious allegiance to Constantinople, the eastern periphery of the Duchy created a gray zone where leaders of smaller centers chose and/or changed religious affiliations depending on the current political situation. Such diversity was also possible because in many areas common people never had to abandon their ancient rites. According to Jerzy Kłoczowski and Antanas Musteikis, in the fourteenth century the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the last mostly pagan state in Europe.[13] Even this late into the religious polarization of the Eastern and Western Christendom and despite strong family ties to Orthodox Christianity, some of the rulers of the Duchy lived in paganism and treated the prospect of conversion as a political tool useful primarily to gain or restructure power in this part of Europe. It seems that from Lublin’s perspective it appeared that if one could create a place that negotiated interests as conflicted as those of the two most dominant powers, Rome and Constantinople, it was possible to think about tolerance as the principle guiding the union of the two states. Jagiełło attempted to envision a political structure, which would unite diverse people without compromising their cultural identity. Writing down rules of a treaty between the two states, defining its military and political consequences, must have been easy in comparison to envisioning a place where different beliefs and worldviews could function peacefully together. Lublin, a place located approximately halfway between the two capitals, Kraków and Vilnius, not only facilitated the process of political negotiations, it also provided a site for symbolic experimentation, unselfconscious representation of a non-hierarchical symbolic order. An almost finished Gothic structure created a rich opportunity for a conceptual engagement with these difficult issues. In this way an attitude of tolerance, a common practice among people living together on the border between Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, was elevated to the rank of the royal site of worship. In places like Lublin centuries ago or in contemporary cities where global migrations create clashes of interests and beliefs, buildings have played a significant role in shaping new ways of thinking about reality. They have supported dynamic cultural exchanges and helped to negotiate conflicts. Built forms have facilitated and recorded these processes by making difficult issues perceivable as lived reality and by preventing such emergent orders from becoming stagnant – their meanings fixed by a dominant interpretation. That is why people who constructed or used such symbolic environments could not verbalize their intentions or draw easy conclusions from their experiences. Although the history of architecture has marginalized these kinds of buildings, they have played a key role in shaping attitudes and sensitivities. In my view, symbolically impure or hybrid structures played a more significant role in the life of people than the seemingly easier-to-interpret monuments of dominant powers that populate the pages of history surveys. Studies of nascent thought and their architectural manifestations will require critical revisions of the epistemological assumptions behind common practices of architectural knowledge but also a new ways to register the non-verbal attributes of architecture.[14]

References: Benjamin, Andrew, Architectural philosophy: repetition, function, alterity (London: The Athlone Press, 2000). Bennett, Tony, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London; New York: Routledge, 1995). Beresford Hope, A. J. B., The Common Sense of Art: A Lecture Delivered in Behalf of the Architectural Museum, at the South Kensington Museum, 8 December, 1858 (London: John Murray, 1858). Foucault, Michel, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, tr. Alan Sheridan (New York: Random House, 1977). Kungel, Robert M., "Pόźnogotyckie cerkwie Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego" in ed. Jerzy Lilejko, Sztuka ziem wschodnich Rzeczypospolitej XVI-XVIII w. (Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, 2000). Kłoczowski, Jerzy, A History of Polish Christianity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). Musteikis, Antanas, The Reformation in Lithuania: Religious Fluctuations in the Sixteenth Century (Boulder: East European Monographs distributed by Columbia University Press, 1988). Panofsky, Erwin, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism (New York: NAL Penguin, 1951). Ruskin, John, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, [1849, 1880] 1989) Rόżycka-Bryzek, Anna, “Bizantyńsko-slowiańskie malowidla w gotyckich kosciołach Polski pierwszych Jagiellonów," in Między Wschodem i Zachodem, Część III, Kultura artystyczna, ed. Tadeusz Chrzanowski (Lublin: Lubelskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 1992). Rόżycka-Bryzek, Anna, Freski w kaplicy zamku lubelskiego (Lublin: Maria Curie-Skłodowka University Press, 2000). Said, Edward W., Culture and Imperialism (New York: Random House, 1994). Saussure, Ferdinand de, Course in General Linguistics, ed. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye, tr. Wade Baskin (New York: Philosophical Library, 1959, [based on lectures from 1906 to 1911 and first published in 1916]). Semper, Gottfried, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, ed. and tr. Harry Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrmann (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). Simson, Otto von, The Gothic Cathedrals: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order in Europe (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1964). Spivak,

Gayatri Chakravorty, In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics

(Methuen: New York and London, 1987).

Notes: [1] By doing so, semioticians assumed existence of the other to the symbolic, a possibility of non-sign reality – material reality without any meaning. Saussure asserted that the signifier does not constitute a meaningful sign until it is interpreted. [2] See, for example, John Ruskin’s discussion of the language-like function of the national style in The Seven Lamps of Architecture and A. J. B. Beresford Hope’s discussion of narratives in the style of Progressive Eclecticism in The Common Sense of Art. [3] Edward Said, for example, studies how such verbal "structures of attitude and reference", were essential in the processes of colonization (Said 1994, p. 52). [4] Knowledge becomes power when it permits or excludes certain thoughts. According to Foucault ”it is not simply at the level of consciousness, of representations and in what one thinks one knows, but at the level of what makes possible the knowledge that is transformed into political investment”, (Foucault 1977, p. 185). [5] This distinction between observable phenomena and normative thought may be seen as analogous to the distinction which Michel Foucault makes in Discipline and Punish, p. 183. [6] The International Research and Exchanges Board supported this part of my research. Mgr. Zygmunt Nasalski, director of the Muzeum Lubelskie, generously granted the permission to study and photograph the chapel. [7] At the time I was studying the chapel, other than purely descriptive and rather outdated Jerzy Siennicki, "Kościół Św. Trójcy w Lublinie" Południe (Zeszyt I, 1924/25), no comprehensive study of the building itself was available. [8] In an unpublished study, Tomasz Gąsiorowski compares this structure to similar Czech and Polish one-column chapels, and concludes that the main volume of the Holy Trinity Chapel in Lublin was most likely constructed during the last quarter of the fourteenth century and consecrated in 1401. [9] Rόżycka-Bryzek’s earlier publication, Bizantyńsko-ruskie malowidła w kaplicy zamku lubelskiego (Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1983), was grounded in similar epistemological assumptions. [10] I discuss this kind of space of representation in “Architecture and the Iconoclastic Controversy” in Medieval Practices of Space, Barbara A. Hanawalt and Michal Kobialka, editors (Minneapolis: University of MN Press, 2000), pp. 101-127. [11] These interpretations of Gothic were introduced by scholars such as Erwin Panofsky and Otto von Simson. Panofsky in his Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism interpreted Gothic architecture as the material manifestation of Scholasticism. Simson, on the other hand, identified Abbot Suger and his design ideas for the structure, windows, and iconographic program in the church of Saint-Denis as the origin of the Gothic style. According to Simson, its material form and especially its interior were intended by Abbot Suger to symbolize the City of God. (Simson, The Gothic, pp. 110-5). [12] Anna Rόżycka-Bryzek has acknowledged this general shift in this and other Polish churches where Gothic architecture coexisted with elements of Russian Byzantine paintings (Rόżycka-Bryzek 1992, p. 338). [13] As such, it was the object of intense missionary work undertaken by the Catholics from the West and the Orthodox from the south (Kłoczowski 2000, p. 55, and Musteikis 1988, pp. 29-36).

[14]

I discuss and test such a possibility of a different way of knowing

architecture in the forthcoming book Architecture of Thought.

|

|

| |

||

| feedback | ||